Improv masterclass at Virginia Commonwealth University. (All photos by Antonio García.)

Improv masterclass at Virginia Commonwealth University. (All photos by Antonio García.)|

This article is copyright 2014 by Antonio J. García and originally was published in the International Trombone Association Journal, Vol. 42, No. 3, July 2014. It is used by permission of the author and, as needed, the publication. Some text variations may occur between the print version and that below. All international rights remain reserved; it is not for further reproduction without written consent. |

Conrad Herwig Masterclass

as told to Antonio J. García

Associate Jazz Editor, ITA Journal

Improv masterclass at Virginia Commonwealth University. (All photos by Antonio García.)

Improv masterclass at Virginia Commonwealth University. (All photos by Antonio García.)

It’s been my delight to host Conrad Herwig on several occasions as a mentor to my students on a variety of topics including improvisation, theory, history, Latin music, ensemble style, music business, and of course the trombone. He has a knack for organizing his advice in a clear and inspiring manner. So I asked him if he’d be agreeable to my capturing his thoughts from his most recent workshops for my students and sharing them with you in the ITA Journal.

General Ideas for Building Creative Improvised

Solos

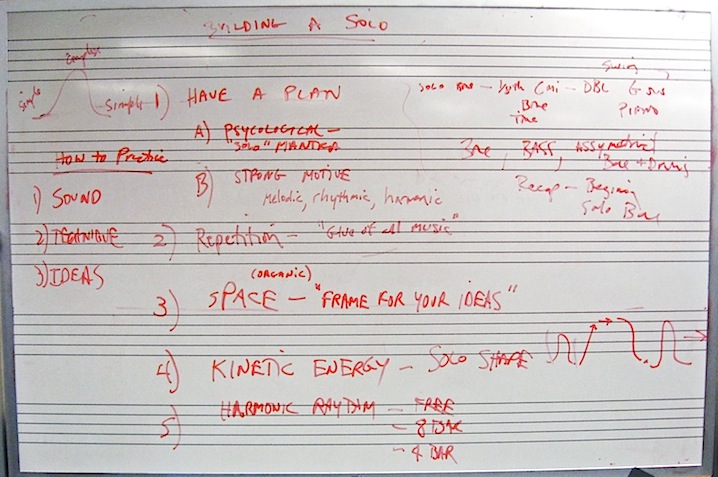

Have a Plan

Before I start a solo, I come up with a jazz mantra (which I repeat silently to myself before I start to play), usually one word, which sets the stage for what I’m about to explore. It might be “grease” on a blues, “chill” or “pocket” on a medium-down tempo, or “longing” or “night” on a ballad. If I’m in an aggressive mood, it might be “burn” or even “shred!” I find that a mantra helps give me sense of psychological direction in the solo.

In terms of musical construction I also look for strong motives that are like the building blocks of my solos. These could be rhythmic, melodic, or even harmonic motives (such as “sheets of sound/against the grain”). We can build on these motives, but focusing on just one will do. Less is more: a little goes a long way.

Deciding on a form for your solo can be critical to its success. A common form is “simple—> complex—> simple.” Start simple; develop the content and intensity; and then return to simple. If you’re into playing “free” jazz, having a form in mind for your collective group improvisation can also create cohesion and unity.

Baseball is a great analogy. Where do you start at bat? Home plate. And no matter how far you advance around the bases, where do you have to go to score? Home plate.

Conrad's musings on the board during his Virginia Commonwealth University masterclass.

Anton von Webern said, “Repetition is the glue of all music.” Think of my favorite repeated figure of all time: the vamp in John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.” Clark Terry once told me, “If you make a mistake, it’s a clam. If you repeat the clam three times in jazz it’s a lick!” Pattern and sequence are related to repetition and are also important in improvisation.

Musical Space

Space is the “frame for your ideas.” Without surrounding space, your ideas won’t have definition. You can also think of it like putting punctuation in your musical statements. The goal is to have clarity and avoid run-on sentences.

Miles Davis was the crown prince of musical space. I remember spending long hours trying to figure out why Miles would lay out just-so-long before continuing or finishing an idea in his solo. Towards the end of Miles’ career, I had the chance to play with him at the Montreux Jazz Festival, re-creating some of the signature Gil Evans arrangements. During a rehearsal I was watching and listening to him play a solo on “Summertime” and noticed his sunglasses sliding down his nose a bit. He paused in the middle of his idea, took his time, and carefully slid his glasses back up into place; then he put the horn to his lips and finished his musical thought on the trumpet. That’s as organic a cause for musical space as I can imagine!

Harmonic Rhythm

Think about how different tunes offer different harmonic rhythm—different rates at which the chord changes move. John Coltrane’s “Impressions” is an example of a tune with an eight-bar harmonic rhythm. Joe Henderson’s “Inner Urge” and Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage” have a four-bar harmonic rhythm. The bridge to “I Got Rhythm” moves in two-bar phrases, and the A section moves in two-beat harmonic rhythm. You can learn to feel these groupings as you solo, and it will help shape your phrasing and the length of your ideas.

Kinetic Energy and Solo Space

Each solo should have its own energy of motion, its kinetic energy, its shape. During the performance of a tune, one soloist might start with lots of energy and wind down. The next might start cool and heat up to a finish. The next might start slowly, build up the energy, and gradually cool down. The variety of solo shapes keeps the presentation from getting predictable.

Getting Down to the Bone

Let’s focus on the trombone. I like to think of trombone-playing as analogous to driving a car. You have the car (the instrument), the engine (the mouthpiece), and the gas tank (the lungs filled with air). A Ferrari with an empty gas tank will not get you anywhere, even though it’s a Ferrari! A custom mouthpiece and expensive horn is only as good as the air supply that blows through it.

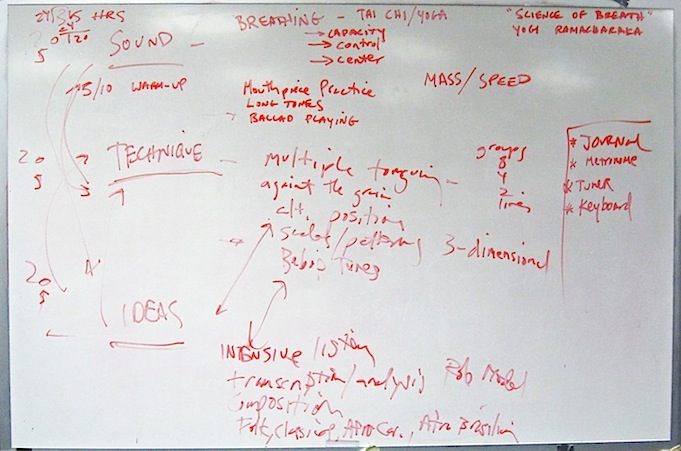

I like to break down the process of jazz trombone-practicing into three elements: sound, technique, and ideas. Players with only one or two of these elements, but not all three, face real limitations in their soloing. So how can we develop all three in our practice?

Conrad's writings during his Virginia Commonwealth University masterclass.

Sound

A lot of elements go into your sound. Let’s start with breathing, which I break up into what I call the 3 C’s: the categories of capacity, control, and center. I work on my lung capacity with concepts I’ve learned from Tai Chi and yoga, as have many other musicians. This is how I find the “center” of my breathing, and breathing properly helps me find the center of myself. When you work on centering breaths, always inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth.

Tai Chi offers such positions as the “Window to Heaven,” which stretches your body in a way very appropriate for maximizing your breathing. And here’s a very user-friendly exercise: inhale for four counts; hold your breath for four; then exhale for four counts. After a few repetitions of this cycle, expand to six counts each, then eventually eight counts each. This will really focus your breathing and slow down your cardio-respiratory system and help create alpha waves, which are critical to the creative process.

The best book ever written on this topic is The Science of Breath: A Complete Manual of the Oriental Breathing Philosophy of Physical, Mental, Psychic and Spiritual Development, a book by Yogi Ramacharaka. You can find plenty of information about it on the Internet, as it’s in the public domain to download). Many spiritual paths emphasize meditation through breathing; and it is interesting to me that even the names for God chosen by some well-known religions are two-syllable words ideal for in-out breath-meditation: Allah, Yahweh, Krishna, and Buddha.

You can work on the control of your breath in many ways. For one, examine your posture when you sit in your performance or rehearsal. I suggest that you should be positioned at the front of your chair, with your center of gravity such that you could instantly stand up without having to shift your balance. This posture aligns your body for optimal breathing and blowing.

In master classes I attended at Interlochen, Michigan the great teacher and former Chicago Symphony Orchestra tuba virtuoso Arnold Jacobs constantly spoke of breathing in and out a using the syllable “HO”: capturing that shape of your oral cavity as you breathe in and out. You will find this really helps relax your throat. I find the concept of blowing warm air very valuable, as it increases air capacity and helps open up the sound.

A simple exercise I call “Blowing Out the Candle” is one I use to work on air control. Hold your index finger out upright a few inches from your mouth, and pretend you are blowing out a candle. Inhale; and then, with your embouchure formed, exhale at your finger so that you can feel the air focused on it. Repeat the exercise, each time moving your finger further away from your mouth. Find the distance at which your airstream seems to lose compression, and work on increasing that focus and distance. This kind of “control breath” is ideal for helping you to move your air efficiently through the trombone.

This brings us to the concepts of another superb teacher with whom I studied, trumpeter and brass guru Don Jacoby, who for years taught privately in Dallas, Texas. While a student at North Texas State University I was fortunate to visit him with some of my trumpet-playing friends. Jake had as much common-sense wisdom on brass-playing as anyone who has picked up an instrument. He would separate breathing and exhalation into two concepts: mass and speed. Mass of air is needed to create dynamic volume, while speed of air is required for building range as well as focus and penetration of your sound over increasing distances. You have to work on both in order to reach your full potential as a brass player.

I believe that one of the best ways to work on your sound and intonation is by focusing on mouthpiece-practice. I recognize that some fine teachers frown on mouthpiece-practice, but I believe most of that concern stems from students who practice on the mouthpiece incorrectly or differently than they do on their horns. I advocate practicing the same correct way on both.

For example, can you buzz on your mouthpiece the same pitches you play on the horn? The horn is just an amplifier of what is happening on the mouthpiece. There’s no way that you will deliver your best sound on the instrument if you are buzzing incorrectly or out of tune.

Try this exercise. Play a long-tone middle B-flat on your horn at mezzo forte; and while sustaining that pitch, smoothly pull the mouthpiece away from the horn while continuing to buzz. Are you hearing the same B-flat on your mouthpiece, or did the pitch waver?

Continue an uninterrupted buzz on the B-flat and gracefully re-insert the mouthpiece into the horn while buzzing. Is the pitch stable?

Once you’ve negotiated how to move your mouthpiece in and out of the horn smoothly without busting yourself in the chops, it’s time to create a two-part cycle in one long-tone breath. Play the long-tone middle B-flat on your horn; pull the horn away from the mouthpiece while continuing to buzz; and then restore the horn to the mouthpiece—all in one breath.

Once you can do that cycle on a B-flat, choose some other medium-range, first-position notes for your long-tone: F and D, for example. Ideally, as you grow, you should be able to accomplish this exercise on any first-position pitch, no matter how high or low; you are sure to notice an improvement in your air, sound, and intonation.

I also encourage you to sit at the piano, play a mid-range octave pair of notes, and glissando from one pitch to the other on your mouthpiece, up and down. You can gradually raise and lower the range of these notes. Don Jacoby used to say, “There are no ‘high’ notes, only notes that are closer to you and further away from you than other notes. Reach out with your air!”

Long-tones are ideal for focus, on the mouthpiece (as above) and on the horn. I realize that long-tones present some boredom for many musicians; so I encourage you to at least address long-tones within the style of jazz that incorporates longer tones into its phrasing: the jazz ballad.

Ballads offer you the opportunity to explore your sound in longer tones. A tune such as “Round Midnight,” “I Can’t Get Started,” or “Body and Soul”—especially taken slowly and lyrically in your practice sessions—can assist in developing your tone. Linger on the longer tones. Play phrases in different octaves to expand your range. Transpose phrases or the entire melody into a different key, which will help expand your range and your overall musicianship.

Ballads offer so many benefits that I find they make ideal warm-ups. After all, as much as we’d like to spend hours warming up, we have a lot of goals to accomplish in our practice. By starting with a ballad you can really get a lot of warming up done in a shorter period of time. The final word on warm-ups is: “Get to the Music!” If your warm-up is more than 15% of your practice session, you need to find a new warm-up.

Technique

I like to divide technical study into five areas: multiple tonguing, playing against the grain, alternate positions, scales and patterns, and bebop tunes.

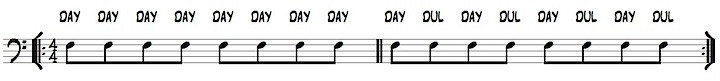

I approach multiple tonguing using “doodle tonguing.” But more accurate syllables to describe it would be “day-dul” and “lay-dul.” Try saying:

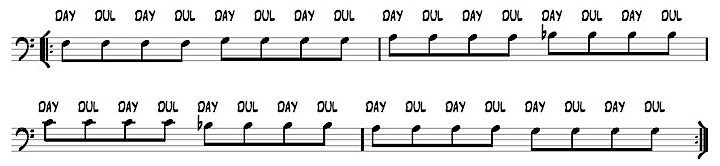

After you can say that easily in a group of eight beats as above, then try groups of four:

...and of two:

Once you can articulate these patterns easily, move them to the horn: play each pattern on a repeated middle B-flat. It may take you some time to get that to be clean; but once you do, you’re ready to start playing lines. This is when you can go back to technical studies like Arban’s and approach them from a new perspective.

Playing against the grain plots “alternate trajectories” of slide versus pitch. You should practice this in a string of positions with the slide moving out while the pitch goes up, for example. And then you can practice it staying in one position, using your air stream to ripple the notes over the adjacent partials in that slide position.

Alternate positions aren’t alternate: they’re necessary! Try playing a tune like Thelonious Monk’s “Well, You Needn’t” in basic slide positions: it’s so much work. But with alternate positions and some against-the-grain placement, it’s as if the tune were written to fit the trombone.

Bebop tunes are the vocabulary with which you can really learn your instrument in a jazz context. For a trombonist, playing a Charlie Parker melody is to jazz what practicing a Bach Cello Suite is to classical music: each is inherently rich in the three dimensions of music.

Ideas

Those three dimensions would be time, melody, and harmony. All music happens in those three dimensions. So when you practice a scale, don’t just “run a scale.” Put it into a rhythmic, melodic, or harmonic context. Make music of it. Now you’re practicing ideas!

You can gain ideas by intensive listening to great musicians, live and recorded. You should transcribe and analyze the solos of your musical role models, learning everything you can from them, and spending time with the aspects of their playing that resonates with what you are hearing in your head. Study composition, and not just in a purely jazz vein. Remember, improvisation is spontaneous composition. Learn what folk, classical, Afro-Cuban, and Afro-Brazilian compositional styles can teach you. Then all your ideas begin to overlap, to cross over from one genre to another.

With a Virginia Commonwealth University Small Jazz Ensemble.

Putting It Together

Some musicians might practice randomly and still improve. You don’t need an organized system of practice when everything’s going great. But when you’re not progressing as well as you feel you should, not learning as broadly and as concentrated a way as you should, not feeling as inspired as you should, that’s when you need a system.

Work on having a plan for organizing a solo. Exploit repetition; exploit space. Examine the harmonic rhythm of the music you’re learning. Plot the kinetic energy you are looking for in your solo shapes. Always work on your sound, technique, and ideas, making every note that comes out of your horn music—music that exists in the realms of time, melody, and harmony. This is a system worth having in your pocket at all times.

Some people listen to jazz soloists and think, “Yeah, that soloist is lucky s/he’s so good”—as if it just happened that way. But musicians spend lifetimes building the synaptic pathways that form our actions and reactions. I say, “Yeah: the more I practice, the luckier I get.”

Recent Discography as a Leader:

THE TIP OF THE SWORD (2011)

THE LATIN SIDE OF HERBIE HANCOCK (2010)

THE LATIN SIDE OF WAYNE SHORTER (2008)

SKETCHES OF SPAIN Y MAS (2006)

OBLIGATION (2005)

QUE VIVA COLTRANE (2005)

ANOTHER KIND OF BLUE: THE LATIN SIDE OF MILES DAVIS (2004)

New York jazz trombonist Conrad Herwig has recorded 20 albums as a leader in addition to contributing to nearly 200 other recording sessions with some of the most notable artists in jazz. He has performed and recorded with Miles Davis, Joe Henderson, Eddie Palmieri, Tito Puente, Frank Sinatra, Joe Lovano, and Tom Harrell, among many others. He holds three GRAMMY® nominations in the “Best Latin Jazz Recording” category. Visit his website at <www.conradherwig.com>.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Antonio J. García is a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Jazz Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he directed the Jazz Orchestra I; instructed Applied Jazz Trombone, Small Jazz Ensemble, Jazz Pedagogy, Music Industry, and various jazz courses; founded a B.A. Music Business Emphasis (for which he initially served as Coordinator); and directed the Greater Richmond High School Jazz Band. An alumnus of the Eastman School of Music and of Loyola University of the South, he has received commissions for jazz, symphonic, chamber, film, and solo works—instrumental and vocal—including grants from Meet The Composer, The Commission Project, The Thelonious Monk Institute, and regional arts councils. His music has aired internationally and has been performed by such artists as Sheila Jordan, Arturo Sandoval, Jim Pugh, Denis DiBlasio, James Moody, and Nick Brignola. Composition/arrangement honors include IAJE (jazz band), ASCAP (orchestral), and Billboard Magazine (pop songwriting). His works have been published by Kjos Music, Hal Leonard, Kendor Music, Doug Beach Music, ejazzlines, Walrus, UNC Jazz Press, Three-Two Music Publications, Potenza Music, and his own garciamusic.com, with five recorded on CDs by Rob Parton’s JazzTech Big Band (Sea Breeze and ROPA JAZZ). His scores for independent films have screened across the U.S. and in Italy, Macedonia, Uganda, Australia, Colombia, India, Germany, Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico, Israel, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. He has fundraised $5.5 million in external gift pledges for the VCU Jazz Program, with hundreds of thousands of dollars already in hand.

A Bach/Selmer trombone clinician, Mr. García serves as the jazz clinician for The Conn-Selmer Institute. He has freelanced as trombonist, bass trombonist, or pianist with over 70 nationally renowned artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, George Shearing, Mel Tormé, Doc Severinsen, Louie Bellson, Dave Brubeck, and Phil Collins—and has performed at the Montreux, Nice, North Sea, Pori (Finland), New Orleans, and Chicago Jazz Festivals. He has produced recordings or broadcasts of such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Jim Pugh, Dave Taylor, Susannah McCorkle, Sir Roland Hanna, and the JazzTech Big Band and is the bass trombonist on Phil Collins’ CD “A Hot Night in Paris” (Atlantic) and DVD “Phil Collins: Finally...The First Farewell Tour” (Warner Music). An avid scat-singer, he has performed vocally with jazz bands, jazz choirs, and computer-generated sounds. He is also a member of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (NARAS). A New Orleans native, he also performed there with such local artists as Pete Fountain, Ronnie Kole, Irma Thomas, and Al Hirt.

Mr. García is a Research Faculty member at The University of KwaZulu-Natal (Durban, South Africa) and the Associate Jazz Editor of the International Trombone Association Journal. He has served as a Network Expert (for Improvisation Materials), President’s Advisory Council member, and Editorial Advisory Board member for the Jazz Education Network . His newest book, Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading (Meredith Music), explores avenues for creating structures that correspond to course objectives. His book Cutting the Changes: Jazz Improvisation via Key Centers (Kjos Music) offers musicians of all ages the opportunity to improvise over standard tunes using just their major scales. He is Co-Editor and Contributing Author of Teaching Jazz: A Course of Study (published by NAfME), authored a chapter within Rehearsing The Jazz Band and The Jazzer’s Cookbook (published by Meredith Music), and contributed to Peter Erskine and Dave Black’s The Musician's Lifeline (Alfred). Within the International Association for Jazz Education he served as Editor of the Jazz Education Journal, President of IAJE-IL, International Co-Chair for Curriculum and for Vocal/Instrumental Integration, and Chicago Host Coordinator for the 1997 Conference. He served on the Illinois Coalition for Music Education coordinating committee, worked with the Illinois and Chicago Public Schools to develop standards for multi-cultural music education, and received a curricular grant from the Council for Basic Education. He has also served as Director of IMEA’s All-State Jazz Choir and Combo and of similar ensembles outside of Illinois. He is the only individual to have directed all three genres of Illinois All-State jazz ensembles—combo, vocal jazz choir, and big band—and is the recipient of the Illinois Music Educators Association’s 2001 Distinguished Service Award.

Regarding Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading, Darius Brubeck says, "How one grades turns out to be a contentious philosophical problem with a surprisingly wide spectrum of responses. García has produced a lucidly written, probing, analytical, and ultimately practical resource for professional jazz educators, replete with valuable ideas, advice, and copious references." Jamey Aebersold offers, "This book should be mandatory reading for all graduating music ed students." Janis Stockhouse states, "Groundbreaking. The comprehensive amount of material García has gathered from leaders in jazz education is impressive in itself. Plus, the veteran educator then presents his own synthesis of the material into a method of teaching and evaluating jazz improvisation that is fresh, practical, and inspiring!" And Dr. Ron McCurdy suggests, "This method will aid in the quality of teaching and learning of jazz improvisation worldwide."

About Cutting the Changes, saxophonist David Liebman states, “This book is perfect for the beginning to intermediate improviser who may be daunted by the multitude of chord changes found in most standard material. Here is a path through the technical chord-change jungle.” Says vocalist Sunny Wilkinson, “The concept is simple, the explanation detailed, the rewards immediate. It’s very singer-friendly.” Adds jazz-education legend Jamey Aebersold, “Tony’s wealth of jazz knowledge allows you to understand and apply his concepts without having to know a lot of theory and harmony. Cutting the Changes allows music educators to present jazz improvisation to many students who would normally be scared of trying.”

Of his jazz curricular work, Standard of Excellence states: “Antonio García has developed a series of Scope and Sequence of Instruction charts to provide a structure that will ensure academic integrity in jazz education.” Wynton Marsalis emphasizes: “Eight key categories meet the challenge of teaching what is historically an oral and aural tradition. All are important ingredients in the recipe.” The Chicago Tribune has highlighted García’s “splendid solos...virtuosity and musicianship...ingenious scoring...shrewd arrangements...exotic orchestral colors, witty riffs, and gloriously uninhibited splashes of dissonance...translucent textures and elegant voicing” and cited him as “a nationally noted jazz artist/educator...one of the most prominent young music educators in the country.” Down Beat has recognized his “knowing solo work on trombone” and “first-class writing of special interest.” The Jazz Report has written about the “talented trombonist,” and Cadence noted his “hauntingly lovely” composing as well as CD production “recommended without any qualifications whatsoever.” Phil Collins has said simply, “He can be in my band whenever he wants.” García is also the subject of an extensive interview within Bonanza: Insights and Wisdom from Professional Jazz Trombonists (Advance Music), profiled along with such artists as Bill Watrous, Mike Davis, Bill Reichenbach, Wayne Andre, John Fedchock, Conrad Herwig, Steve Turre, Jim Pugh, and Ed Neumeister.

The Secretary of the Board of The Midwest Clinic and a past Advisory Board member of the Brubeck Institute, Mr. García has adjudicated festivals and presented clinics in Canada, Europe, Australia, The Middle East, and South Africa, including creativity workshops for Motorola, Inc.’s international management executives. The partnership he created between VCU Jazz and the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music at the University of KwaZulu-Natal merited the 2013 VCU Community Engagement Award for Research. He has served as adjudicator for the International Trombone Association’s Frank Rosolino, Carl Fontana, and Rath Jazz Trombone Scholarship competitions and the Kai Winding Jazz Trombone Ensemble competition and has been asked to serve on Arts Midwest’s “Midwest Jazz Masters” panel and the Virginia Commission for the Arts “Artist Fellowship in Music Composition” panel. He was published within the inaugural edition of Jazz Education in Research and Practice and has been repeatedly published in Down Beat; JAZZed; Jazz Improv; Music, Inc.; The International Musician; The Instrumentalist; and the journals of NAfME, IAJE, ITA, American Orff-Schulwerk Association, Percussive Arts Society, Arts Midwest, Illinois Music Educators Association, and Illinois Association of School Boards. Previous to VCU, he served as Associate Professor and Coordinator of Combos at Northwestern University, where he taught jazz and integrated arts, was Jazz Coordinator for the National High School Music Institute, and for four years directed the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. Formerly the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Northern Illinois University, he was selected by students and faculty there as the recipient of a 1992 “Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching” award and nominated as its candidate for 1992 CASE “U.S. Professor of the Year” (one of 434 nationwide). He is recipient of the VCU School of the Artsí 2015 Faculty Award of Excellence for his teaching, research, and service and in 2021 was inducted into the Conn-Selmer Institute Hall of Fame. Visit his web site at <www.garciamusic.com>.

If you entered this page via a search

engine and would like to visit more of this site,

For further information on the International

Trombone Association Journal, see