Learning Swing via Afro-Cuban Style

by Antonio J. García

Think of the Count Basie Orchestra performing the great swing tune “Shiny Stockings”: how each section and player seem to move the lines forward with such exquisite timing. Recall that same band delivering the classic swing ballad “Lil’ Darlin’”: what a groove!

When less-experienced ensembles—vocal or instrumental—perform these tunes and similar, we seek that high a standard of swing groove. If we fail—whether on a sassy “shout” section or a whispering ballad—it’s typically because our ensemble lacks a shared concept of the swing groove; so we don’t place the downbeats and upbeats definitively within any one beat. Since all swing comes from Afro-Cuban, introducing or re-introducing the Afro-Cuban 6/8 feel can lock in that groove for anything from “Lil’ Darlin’” to “Shiny Stockings.”

If you’re reading this and are surprised to hear that all swing comes from Afro-Cuban, be assured that you’re not alone. But it’s absolutely true; and we need to spread the word because the musical benefits are immense.

I had the great pleasure recently of workshopping an ensemble that was performing a terrific arrangement that incorporated shifts from swing to Afro-Cuban styles and back. The young musicians were dedicated, talented, and extremely musical in their delivery. But though the arrangement even included points where different melodic lines were to inflect swing and Afro-Cuban styles simultaneously, the ensemble members were unaware that swing comes from Afro-Cuban. Knowing even just the most basic 6/8 Afro-Cuban rhythmic underpinnings can add worlds of maturity to your swing style. And once these fine musicians got a taste of that link, their performance of the music skyrocketed in authentic feel.

I incorporate Afro-Cuban grooves under swing tunes in my ensembles’ rehearsals whenever our swing groove is lacking. If you’ve kept these two styles separate in your own rehearsals, I invite you to read on as to how this can make a positive effect in your own ensemble.

The Prerequisite: Listen!

I believe it is the singer/lyricist Jon Hendricks to whom the following one-word poem regarding jazz is attributed: “LISTEN!” So before I go any further, I must emphasize that one cannot take for granted the importance of experiencing the swing feel before even attempting to perform it. Has every member of your group heard recordings of great instrumental and vocal groups and soloists in this tradition? It is remarkable how many ensembles I encounter in my travels that have not. And is it possible to ensure that your group hears at least one exemplary professional ensemble live in concert? If so, your musicians will grow exponentially from the experience.

A Solution

So often the only words an ensemble might hear from its leader regarding improving swing style are “don’t rush” or “lay back” or “don’t drag.” While often accurate, these instructions lack sufficient detail to communicate well with less-experienced students of the music. What if you could demonstrate to them exactly where the groove should be?

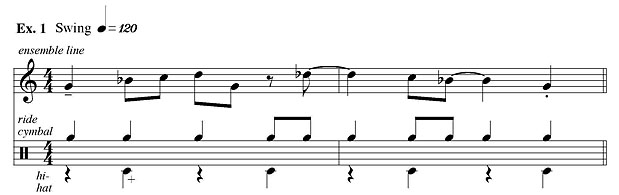

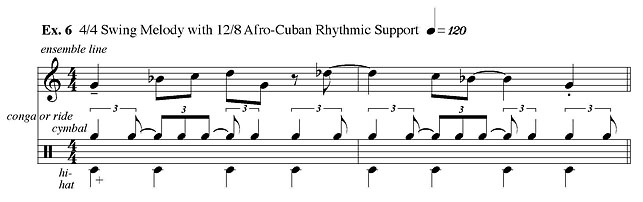

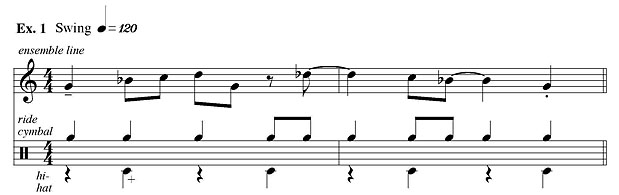

Here’s a melodic line we’ll use as a sample swing phrase for experimentation (Example 1).

The top stave represents, say, the horns or vocals; and the bottom stave represents the two most critical time-keeping portions of a drum set: the ride cymbal and hi-hat. Currently the drums are playing a basic 4/4 swing pattern—but our horns or vocals are supposedly not lining up well within the swing groove.

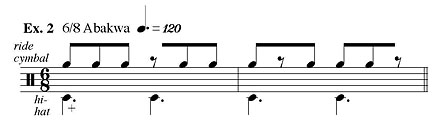

First, let’s explore the powerful solution rooted in the history of swing: the Afro-Cuban groove known most commonly as abakwa and its triplet-feel bell pattern. Here the abakwa pattern is written as two measures of 6/8 (Example 2).

Spend some time singing the upper line while tapping the bottom (hi-hat) rhythm with your hand. Feel the cross-rhythm of the upper grouping of four eighths (three notes plus a rest) played over the lower grouping of three eighths (each dotted-quarter note), as well as across the overall sum of four dotted quarters. If it takes you a while to get it right, enjoy the ride; but it’s critical that you be able to feel this cross-rhythm over the ground beat.

From this abakwa pattern comes a cymbal bell pattern that is commonly played in, say, a “2-3 son clave 6/8 feel” (Example 3).

Again, spend some time singing the upper line while tapping the lower line. Feel the cross-rhythms!

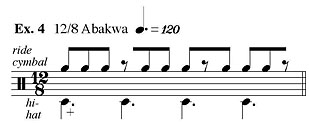

Now that we’ve viewed these rhythms in their indigenous pair of 6/8 measures, let’s re-write the same sounds as in a single bar of 12/8 (Examples 4 & 5): here you see a bar of the abakwa and a bar of the bell pattern.

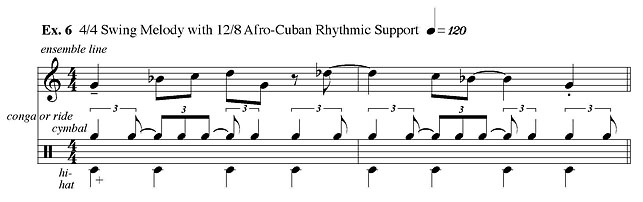

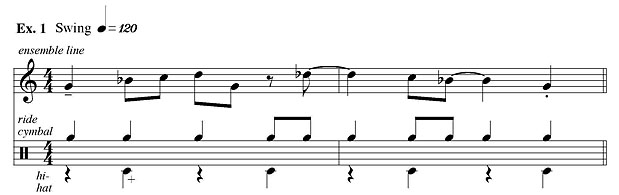

So now we’re set to align these four beats with the four beats of a swing tune’s 4/4 measure. Let’s start with the bell pattern now written as triplets within a single measure of 4/4. If your drummer or conga player were to play what we’ll still call the 6/8 bell pattern under the ensemble’s delivery of the swing melodic line, you’d have Example 6.

Even by yourself you can experience the 6/8 influence by tapping the lowest (hi-hat) line while singing the rhythms of the upper (ensemble) line and then continuing directly into singing the middle (ride cymbal) line. By alternating melody and 6/8 groove, you can easily feel how the two are related.

Have your ensemble vamp/loop a two-bar cycle: two bars playing the melodic line over drums, then two bars drums only, repeating: with each passing cycle, you’ll hear the musicians locking in to the triplet feel of the groove.

Then make a vamp performing two bars of Example 6 followed immediately by two of the swing-accompanied Example 1 (thus horns/vocals do the same all times)—and back again to Example 6, then Example 1.

The triplet-placed timing of the Afro-Cuban phrasing will influence the ensemble’s delivering the same melodic feel over the swing groove that had originally been the challenge. And you didn’t have to repeatedly request “don’t rush” or “lay back” or “don’t drag”—you let the Afro-Cuban groove speak for itself.

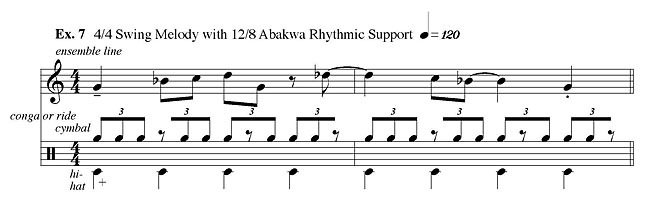

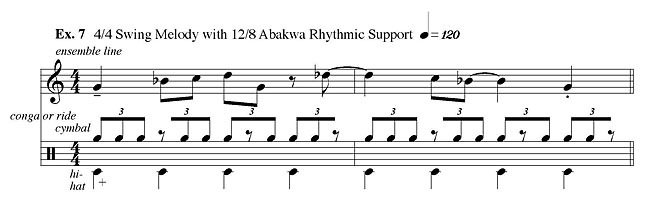

If your group needs a bit more detailed reinforcement, try placing the abakwa pattern (now also notated within a single measure of 4/4) under the ensemble (Example 7).

Some ensembles might find the additional rhythmic attacks helpful; others might find it too much detail. But the principle remains the same: after vamping the melodic phrase over this groove, then make a vamp performing two bars of Example 7 followed immediately by two of the swing-accompanied Example 1—and back again to Example 7, then Example 1.

This is not my original idea, by any means. Long before anyone had thought about this historical link, the triplet divisions of these Afro-Cuban grooves had sown the seeds of blues and swing feel into the turn of the twentieth century—and have infused their essence into medium-tempo 4/4 swing ever since. You can even listen to African drum and mbira masters currently perform music rooted from hundreds of years ago that to the modern jazz musician’s ear clearly sounds like the inflections of swing and blues: adding the Cuban influence in later centuries only made these inflections more pronounced.

Mature rhythm sections feel these 6/8 patterns as the underlying groove between the quarter notes of a walking-bass line or a swing ride-cymbal pattern. The most modern jazz musicians still inflect the occasional middle-triplet accent in their swing solos and accompanying lines.

The Challenge of Swing Ballads

Few grooves reveal more about a jazz ensemble’s maturity than a jazz ballad with swing eighth notes. Whether a vocal or instrumental group, can the musicians place the notes in just the right spot so as to convey the feel intended?

The typical challenge for most ensembles is rushing given notes or entire phrases. This is a fairly natural occurrence because the ballads usually include a number of short quarter notes. These are easier to rush than long, legato quarters.

Allow yourself a visual metaphor: imagine your goal was to hold in the outstretched palm of your hand a dozen pencils, each fitted tightly against the next in a bunch. It would be a fairly easy task, as each pencil is aligned by its neighbor touching it.

But if your goal was to hold a dozen toothpicks—yet each spaced evenly apart at the width of the original pencils—it would be extremely challenging to keep them exactly in place: the slightest movement of your hand could easily roll one or more toothpicks off target. There’s nothing in between them, in the “dead spaces,” to assist in aligning them.

In this visual metaphor, the pencils are legato quarter notes, each smoothly connected to the next by the width of its neighbor and thus easier to maintain in place. The toothpicks are short quarters, a fraction of the pencils’ width, without supportive neighbors to assist in accurate placement and thus easily knocked off target. The typical response by most ensemble directors is “Wait for the beat! Don’t rush!” This usually generates limited and temporary results. What about a way to improve the ensemble members’ perception of the width of the beat surrounding each “toothpick”?

Filling in the Spaces

If the short quarters are rushing because there’s nothing in between them to support their placement, then a clear solution is to provide everyone with the complete picture of the divisions within the beat so that these “toothpicks” can be firmly anchored in context. And the 6/8 Afro-Cuban groove makes the perfect complement to a swing ballad for this purpose.

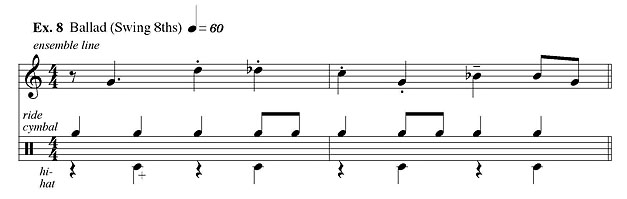

Here’s a melodic line we’ll use as a sample swing ballad phrase for experimentation (Example 8), with the top stave representing the horns or vocals and the bottom the ride cymbal and hi-hat in still a basic 4/4 swing pattern, but slower. Those dots over most of the quarter notes in the upper line are going to invite trouble for the melody’s tempo!

Let’s talk about how such staccato markings might be interpreted. Some ensembles will perform short quarters as fifty percent of the beat or less (as in the classic rendition by the Count Basie Orchestra of “‘Lil’ Darlin’” on The Complete Atomic Basie). While dramatic and accomplished by some very experienced ensembles, this effect can be extremely difficult for a young group to master, as it takes great rhythmic maturity to hold a slow tempo amid such space between these “toothpicks.” It also subtracts much of the potential vocal quality of the melodic line, changing it from lyrical to almost purely instrumental in nature—and most ballads crave a lyrical effect from the instruments involved.

Another interpretation by many is to make each short quarter one third of the beat, an even greater challenge for a younger ensemble.

A third interpretation, which I encourage for all developing ensembles (and which is adopted by many pro groups as well) is to perform short quarters as approximately two-thirds of a beat, promoting a lyrical quality in which each note easily could support a word or syllable. In this Louis Armstrong-inspired phrasing of short notes (as in “Struttin’ with Some Barbeque” on his Hot Five recordings) the space between the notes is less than in either of the previous two scenarios above. But the challenge to most ensembles’ groove often does not entirely disappear. So how best might the group rehearse this style?

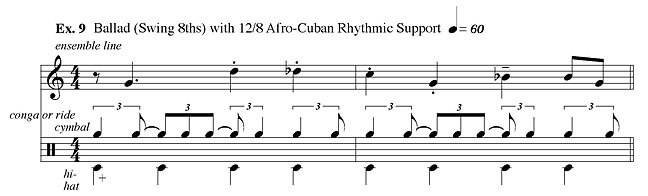

My preferred method is to play—or have a student play—on congas the “6/8” ride cymbal pattern shown atop the bottom stave of Example 9, while the drummer plays the downbeats on the hi-hat.

If there’s no conga player in the ensemble, the drummer could play the ride pattern with brushes or light sticks on the ride cymbal along with hi-hat downbeats. The horns or vocals then either play the entire tune or just vamp the first one or two phrases of the tune for added focus on the groove.

One of the primary weaknesses of many swing-ballad performances is not so much the attacks but the releases of various notes and phrases. So much attention is brought to bear on beginning notes together within the ensemble that the phrase-endings are often relatively ignored. And yet a fundamental element in attacking a note in unison timing is for everyone to release the preceding note together as well, so as to prepare the next entrance.

So it is in these melodic exercises that the full benefit of rehearsing swing ballads with a 6/8 Afro-Cuban underpinning comes to light: the triplet-based conga line not only reinforces when to begin each note but also exactly where to release it.

Once everyone has experienced this unity of groove using the Afro-Cuban bell pattern, count the ensemble off on the chart as written, without congas, and note the marked improvement in the ensemble’s musicality. For when the group’s timing is together, its phrasing improves, as usually does its dynamic ability and often even its intonation!

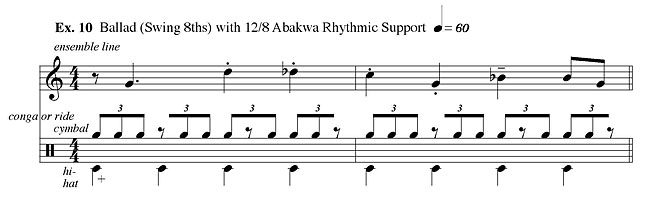

If your group needs more swing eighth-note detail, try (as we did with the medium swing example) placing the abakwa pattern under the ensemble (Example 10), using congas or lightly sticked ride cymbal.

Again, some ensembles might find the additional rhythmic attacks distracting; others will benefit from it.

If your ensemble needs assistance during a loud “shout” section of the ballad, then in rehearsal replace the swing ride-cymbal pattern completely with one or the other Afro-Cuban pattern. Played strongly, it will provide the entire ensemble with a full perspective of the width of each beat in the measure.

Full Circle

I’ll state outright that not all swing is fully triplet-based: there’s a lot of variance between the first and second eighth-notes in a given musician’s swing style. But I’ll also state that when it comes to unifying an ensemble’s attacks, releases, and overall groove for medium-swing and ballad-swing arrangements, exposing ensembles of any age to the underpinnings of 6/8 Afro-Cuban have brought the most profound and stable improvement I’ve witnessed. You’ll not only give your musicians a great tool with which to swing, you’ll reconnect them to the critical, historical link between swing and Afro-Cuban.

There’s no better way to bring an ensemble into the heart of what really makes jazz swing than delving into its Afro-Cuban roots.

------------begin sidebar---------

Books

· Malabe, Frank & Weiner, Bob (1994). Afro-Cuban Rhythms for Drumset, Alfred Music Publishing.

There are many wonderful sources from which to learn the basics of Afro-Cuban and its relationship to swing. My favorite by far is this book with CD. It’s widely available from local dealers and bookstores as well as from the Jamey Aebersold web site at <www.jazzbooks.com>. The book includes notated musical examples (performed on the included CD), historical and cultural background, a glossary of terms, and more. Regardless of whether or not you are a drummer, this book teaches you the basics of the grooves and why.

· Mauleón, Rebeca (1993, 2005). The Salsa Guidebook for Piano & Ensemble, Sher Music.

Available locally and at <www.shermusic.com>, the book conveys superb perspectives but across piano, bass, drum set, and salsa percussion instruments.

Articles

The following articles by the author are listed here because

of their direct pertinence to elements of phrasing:

- “Where's the Beat?, Part 1,” JAZZed, Vol. 3, No. 1, December 2007/January 2008.

- “Where's the Beat?, Part 2,” JAZZed, Vol. 3, No. 2, March 2008.

- “Learning Swing Feel or How to Sculpt an Elephant,” ITA Journal, International Trombone Association, Vol. 34, No. 2, April 2006.

- “Improve Your Groove, Part 1,” School Band and Orchestra, Vol. 2, No. 8, October 1999.

- “Improve Your Groove, Part 2,” School Band and Orchestra, Vol. 2, No. 9, November 1999.

- “Count-Offs Set the Groove,” The Instrumentalist, Vol. 52, No. 4, November 1997.

- “Fine-Tuning Your Ensemble’s Jazz Style,” Music Educators Journal, Music Educators National Conference, Vol. 77, No. 6, February 1991.

- “Pedagogical Scat,” Music Educators Journal, Music Educators National Conference, Vol. 77, No. 1, September 1990.

Recordings

Swing

· Louis Armstrong The Hot Fives and Hot Sevens, Vol. III—Sony/Columbia Jazz

Masterpieces CK-44422 (1989).

· Count Basie Orchestra The Complete Atomic

Basie—Blue Note 28635 (1958, reissued 1994).

· Frank Sinatra Sinatra at the Sands—Warner Brothers 46947 (1966, reissued

1998).

· Lester Young with the Oscar Peterson Trio—Polygram

Records 521451-2/Verve 314-521451-2 (1952, reissued 1997).

· Mel Tormé with the Meltones Back in Town—Verve

314 511 522-2 (1991).

· Ella Fitzgerald & Count Basie Ella & Basie:

On the Sunny Side of the Street—Polygram

539059 (1984, 1990, 1997, originally released 1963 as Ella and Basie).

Afro-Cuban

· Dizzy Gillespie Compact Jazz—Mercury

832 574-2 (1987).

Listen to “A Night in Tunisia,” as recorded in 1954 originally on Afro (Norgran MGN-1003). In this version he maintains the 6/8 Afro-Cuban rhythm-section feel under his swing-like lines. To my ear, this is the best-recorded illustration ever of the linkage between Afro-Cuban and swing.

· H.M.A. Salsa/Jazz Orchestra California Salsa—Sea Breeze CDSB-110 (1991).

· Mambo All-Stars The Mambo Kings—Elektra 62505 (1992, reissued 2000).

Here you’ll find not only a wide range of instrumentalists but also the incomparable vocalist Celia Cruz.

· Vocal Sampling Una Forma Mas—Sire/Elektra 61792-2 (1995).

African Drum & Mbira

· Master

Drummers of Dagbon, Vol. 2—Rounder CD 5046 (1992).

Listen to musicians of Ghana, West Africa drum. Near the beginning of “Nantoo Nimdi” you can hear a 3-2 clave feel; in “Zambarima-Waa” hear cross-rhythms that influenced jazz; in “Suberima Kpeeru” hear an uptempo groove that would be at home in a modern setting.

· The Soul of Mbira—Nonesuch Explorer 79704-2 (2008, 2002, originally a 1973 recording).

Listen to musicians of Zimbabwe, Southern Africa play mbira. In “Nayamaropa” hear bluesy vocals; in “Kuyadya Hoye” hear jazz’s future cross-rhythms; in “Nhimutimu” hear one remarkable soloist perform an ensemble’s worth of layers, including a walking bass feel.

------------end sidebar---------