Jazz Bass: Crawl Before You Walk

by Tom Warrington

Rhythm Section as Foundation

Jazz ensemble directors must understand the importance of the rhythm section. So many times at festivals and contests I hear bands that have a fine horn ensemble: it's easy to tell that most of the rehearsal effort was concentrated there. Yet the rhythm sections are spoiling the effort, functioning as some secondary embellishment–like the frosting on a cake.

This thinking has to be reversed: the strength generated by the rhythm section provides the foundation from which everything else grows. The time feel in the rhythm section–especially between the drummer and bassist–has to provide the power to drive the ensemble forward; and without this power the whole effort is considerably weakened. The rhythm section is actually the bottom layer of the "cake."

The lack of attention to rhythm sections is often most apparent at the bass chair. This is probably due in part to an attitude carried over from the old garage-band days: a band with three guitars and a drummer would select the worst guitarist to become the bassist. Many young bass players have not had the solid fundamental training that horn players receive coming up through the traditional band and orchestra programs. Soon many directors realize: "The rhythm section needs to sound strong, but my bass player is a struggling beginner. What do I do?" Once the primary step of identifying this problem is past, there are some important techniques to help a beginning bassist.

An Interpretative Art

First, understand that the rhythm section is different. Unlike horn parts, which are to be executed exactly as they appear on the page, rhythm-section parts serve only as a guide at best–and at worst, a blueprint for sounding really dumb. Unfortunately some composers persist with the aforementioned conception of the rhythm section as a secondary add-on: they either don't know how to create meaningful rhythm parts or don't bother to do so. The result is usually a sketchy part with some chord changes and some elementary bass lines–a part relying heavily on the experience of the player. Without applicable experience the beginner simply has no chance to sound good. Directors may provide some information about scales, chord tones, and other harmonic material; but for the beginner, this data (combined with partially written lines) becomes an insurmountable pile of choices.

Time is of the Essence

In order to solve this problem, guide the beginning bassist into a shift of emphasis: away from focusing on playing the right notes and playing the written part exactly–and towards generating a feel by playing notes at the right time. This is an extremely important concept, deserving a second utterance: "Playing the right notes is not as important as playing notes at the right time." On many old recordings, especially CD reissues where the bass notes can actually be heard via digital re-mastering, the notes aren't always so good–but the time feel and rhythmic pulse are. So begin to recondition the beginning bassist to understand his or her role in the ensemble: to combine forces with the drummer and provide that strong, rhythmic foundation–the number one essential element of a good bass line.

Specifically, help the beginning bass player focus on listening rather than reading. Set aside the chart and just have the bassist and drummer play something simple: just one repeated pitch in quarter notes for the bass while both concentrate on the alignment of the bass note with the ride-cymbal beat...then any quarter notes from the bassist (Example 1):

|

Then try the blues, with the bass playing repeated quarter-note chord roots while both again concentrate on the alignment of the beats (Ex. 2):

|

Make sure that they're really focusing on generating a consensus of time without worrying about notes. Have them express openly any feelings of rushing or dragging; have them play with a metronome and play-along recordings; and continue to stress listening to each other and aligning bass and drums as the primary focus of concentration.

Go through a chart, making sure that the form and basic structure are clearly indicated; and where only lines exist, pencil in some chord changes. Written lines can be avoided in favor of changes, excepting areas where the bass has a unison line with another section. Keep the changes basic and in a consistent harmonic rhythm. Then get the drummer and bassist to work together again on this form as they did on the blues.

Beyond Roots

Once their rhythmic alignment is achieved (no small feat!), the rhythmic foundation is in place; and the other two elements of a quality bass line can be examined and added: harmonic/structural foundation and counter-melody. Once bassists learn notes' locations on the instrument well enough to find the chord roots without difficulty, they should expand their arsenal with some chord tones and passing tones.

This can be accomplished without the encumbrance of massive theoretical study. For example, have the player add one simple passing tone–a leading tone–to the repeated chord-root technique: every time the chord changes, the bass plays a leading tone (a half-step below the next chord root) on the beat just before the chord changes (Ex. 3):

|

Remember the primary focus: not so much playing the "right notes" but rather notes at the right time, aligned with the ride-cymbal beat.

Once the beginning bassist is comfortable with these primary techniques of chord chart-reading and generating a good time feel with the drummer, there are several ways of embellishing the basic concept. For example, where one chord exists for at least four beats, a lower neighboring tone might be included in the line along with the leading tone. Thus rather than playing three chord roots (on beats one through three) and then the leading tone (on beat four), the lower neighboring tone could sometimes be inserted on beat two (Ex. 4):

|

Another alternative to playing three chord roots in a row is to insert the fifth (Ex. 5), which introduces the idea of chord outlining:

|

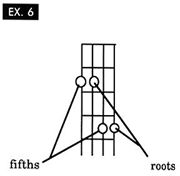

You can show a student how to find the fifth of any chord root as a pattern-shape on the bass fingerboard–without delving into any theoretical discussion. The fifth is found on the adjacent lower string, directly across from the chord root–or on the adjacent higher string, two frets above (Ex. 6):

|

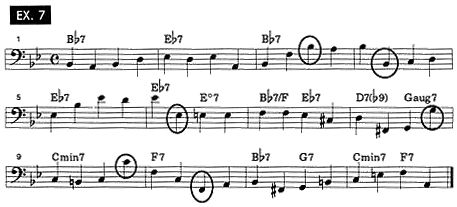

Continuing to build on this pattern-basis, the student could occasionally shift up or down an octave to play another root (Ex. 7);...

|

or add an extra leading tone, creating two half-step approaches (Ex. 8);...

|

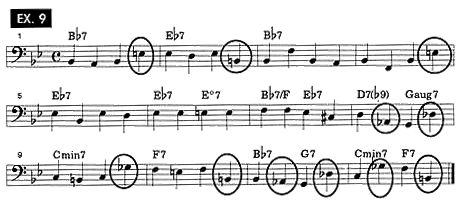

use occasional approaches from a half-step above the next chord root (Ex. 9);...

|

or even insert a fifth between a high and low chord-root, creating a basic "drop" concept (Ex. 10):

|

These multiple possibilities allow a young bassist to continue to concentrate on generating a strong time feel while creating some very interesting bass lines–without too much reading or theory getting in the way. As the player gets stronger and more comfortable with this process, the ability to sustain a continuum of concentration will increase. This skill–maintaining a level of intensity over an extended time period–is so important in order for a rhythm section to bring a piece of music to life; and it will begin to evolve naturally as players listen and really tune in to each other.

Getting Set

Other basic points should help to unify the rhythm section. Though it would seem obvious that the section members should be set up in close proximity to one other so that they can hear and function as a unit, I still see ensembles with the drummer up on a riser and the pianist and bassist down in front some twenty to thirty feet away. It is impossible to play together when you are that far apart.

The bass sound is also very important. Try to get a balanced sound from the bass (acoustic or electric) that emulates the sound of an unamplified acoustic bass. Pay attention to amp settings, keep the volume audible but low, and set the tone controls so the "meat" of the sound in the lower-middle range is present without ultra-low boom or high-end twang. The bassist's technique can also assist the sound. Make sure that the left hand is holding down the notes for their full value, connecting one note smoothly to the next without gaps. An electric bassist's right hand can also pluck the strings more toward the end of the fingerboard: this better imitates the acoustic-bass attack.

Resources

There are literally tons of material for further study. I grew up in the '60s, listening to the Beatles and rhythm-and-blues groups. The Beatles' tunes had logical harmonic structures, and the bass lines functioned well without being overly complex. Later I studied Bill Evans for the sheer beauty of the harmonic flow, and this pursuit is always a fruitful one for aspiring bassists. In the big band realm, the early Thad Jones & Mel Lewis recordings include masterful bass lines composed by Thad that are worthy of study. There are also lots of good texts out there, including Rufus Reid's The Evolving Bassist, the materials included in my author's statement below, and those referenced in Steve's Houghton's article later in this same issue of the JEJ. But the most important assignments for the beginning bassist are to listen to lots and lots of the music you are trying to emulate, play as much with other players as you possibly can, and have some fun while you're at it!

Tom Warrington is currently one of the busiest bass players in Los Angeles, having moved there from New York City seventeen years ago. He has toured and recorded with a long list of great artists, including Freddie Hubbard, Buddy Rich, Denny Zeitlin, Randy Brecker, Bob Florence, Billy Childs, Mose Allison, Terry Trotter, and Joe LaBarbera; and his playing is featured in Jodie Foster's film, "Little Man Tate." Tom's active schedule of studio recording recently included a GTE commercial with Herbie Hancock: he performs concerts, offers clinics, and tours with many different jazz groups. Highly regarded as a clinician and educator, he has also published a variety of musical works (having received a Master of Music degree in Composition from the University of Illinois) and instructional materials (including The Contemporary Rhythm Section text and video series and Essential Styles play-along series.